The Frag Tray

At the end of June, while fresh traumas multiplied in the media like the bone-collecting Mind Flayer in Stranger Things, I was feverishly finishing an essay about another, more seasoned crisis: the impact of the Covid pandemic on nurses. In our current age, it seems we cannot recover from one despair without having to face the next.

As part of the research process, I interviewed my friend Courtney, an acute care nurse practitioner who’s fought on the frontlines of the Covid war since 2020. We met up at a posh hotel restaurant and sipped mimosas while I recorded some of her most horrific pandemic war stories. Our dainty arugula salads stood in bizarre contrast to Court’s description of a serial killer virus that branded its victims with fatal inflammation, blood clots, and brittle, pockmarked lungs impervious to oxygen.

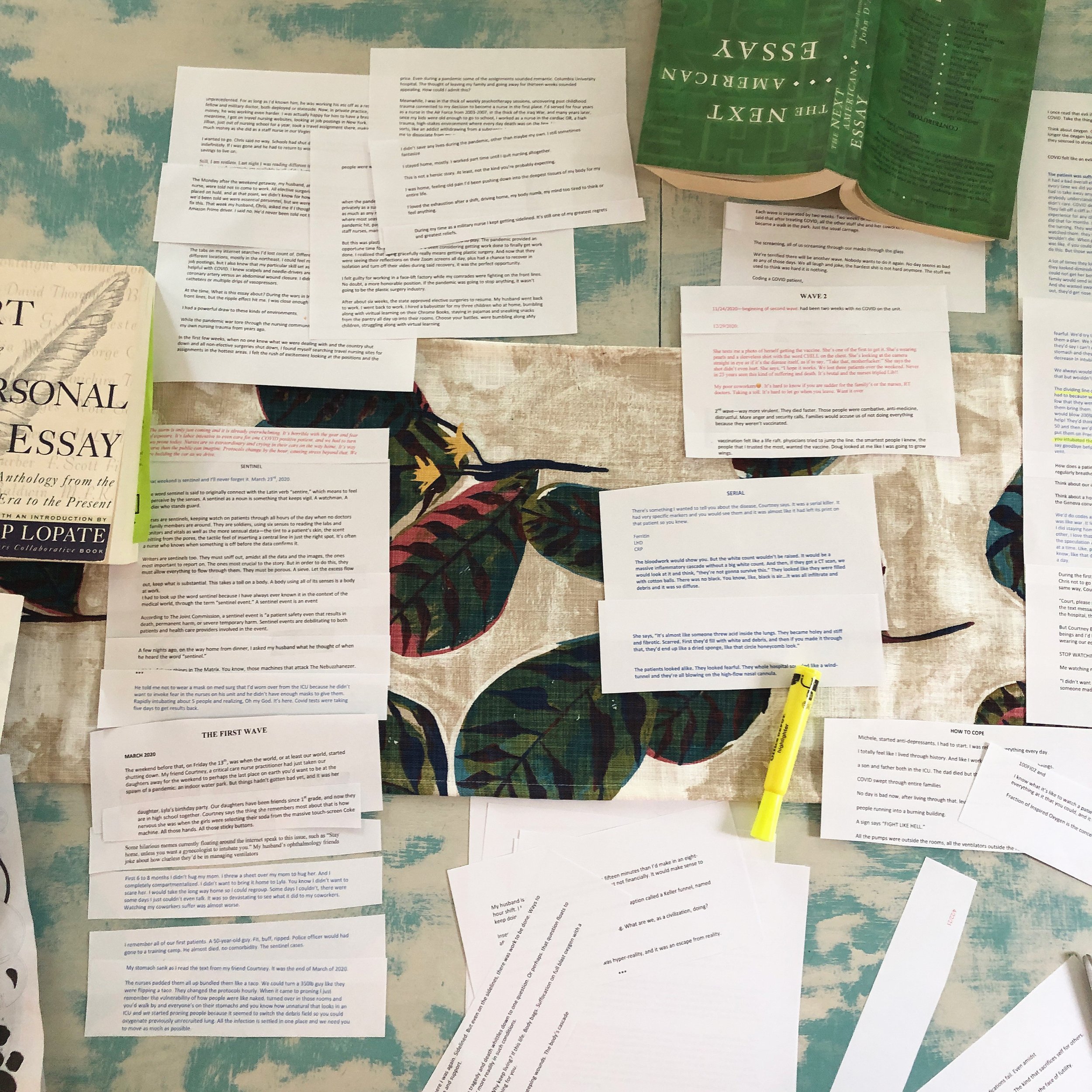

Our interview yielded over two hours of audio, and by the time I transcribed twenty-ish pages of single-spaced weighty words, my body felt as heavy as a tombstone. It was too much to take in on my computer screen, so I printed out the text, sliced it into paragraphs, and splayed the scraps on my dining room table in categories that might go together.

Where is the story? I thought. AND HOW THE HELL AM I GOING TO TELL IT?

According to memoirist Marion Roach Smith, this is the question that causes writers to drink liquor straight out of the bottle. Because it all seems like such a good idea to write of your family’s immoderate behavior, your son’s illness, your marriage, your child’s suicide, or your recovery… until someone actually asks you how you’re going to do it.

I was writing on deadline and I had a 4,000-word limit. I wanted to somehow weave Courtney’s and my nursing experiences together and I wanted to do her justice. I knew I needed a latch—some sort of framework that would allow me descend and resurface without drowning in the content’s dark density and intensity. As I looked for connections between all the paper scraps, I realized that the answer was right in front of me. Trauma narratives defy the linear, plot-based story structures we’re force-fed in popular TV and novels. They come out as disordered sensory fragments, and the first step in writing about traumatic experiences is to use this to your advantage, to let the fragments speak for themselves.

The word fragment makes me think of the abbreviation “frag,” which makes me think of my experiences as an OR nurse. When I worked in the orthopedic room, we often used an instrument set called “the frag tray” to repair broken bones. There was a mini frag tray for tiny bones, as well as a small and large frag tray, each containing the tools necessary to reduce the fracture and bind the pieces together. The plates and screws in the mini frag tray, commonly used for foot fractures, were impossibly tiny—cute, even—mere millimeters of steel that made it possible for a patient to walk again. As I limped through my own writing process, I wanted a literary equivalent to a mini-frag screw, and that’s when it hit me:

The asterisk!

That cute *screw-shaped* literary tool with starry notches that binds broken words together was at my disposal! I could plug it between my fractured vignettes, allowing the small bits to stand alone while also telling a much larger story—one based on pattern and language and theme rather than plot and chronology. Once the fragments were fastened on the page, I could better see the connections and order, what needed to stay or go or deepen. Was this structure the most polished way I could tell this story? Probably not. Was it kind of lazy? Maybe. But, as essayist Jaime Green writes: It made it easier to write. AND I LIKED IT.

I submitted my fragmented essay to the journal I was writing for and I hope it will get published. If I’d had more time and mental bandwidth, perhaps I could have let the figurative bones of my essay heal and explant the asterisk-screws, allowing the story to flow with flawless verbal transitions and a voluptuous narrative arc, but I’m learning that this line of thinking equates to creative-paralysis. I did the best I could with the resources I had and that was good enough for me. I learned a lot in the process, and I was able to bear witness to the haunting stories Courtney has carried inside of her for past few years, which was the biggest gift of all.

So, in our current climate of near-constant collective trauma, consider this month’s post an official invitation to let your mind work, and write, with its own brokenness, regardless of the outcome. Arrange on the page the scraps of images you already have access to. Use the metaphoric mini-frag screws at your personal disposal, whether that’s a liberal use of asterisks, or just having a friend to text when you’re about to plummet into shadowy monster of your own traumatic past. I’ve found that having some screws, or belays (as my therapist calls them), is the kindest, most humane way to do the work. Eventually, with enough small fragments in place, the larger narrative will emerge, and it probably won’t be the one you thought you knew.

If you’d like to read some gorgeous fragmented essays that illustrate what the hell I’m talking about, check out “Fragmented Narratives are Broken, Independent, and Honest” by Sinead Gleeson @ LitHub, as well as this stunner about being a “good-enough” writer by Jaime Green @ Catapult. And finally, please don’t miss “Shutter Speed” by Cameron Gearen @ Autofocus Lit, a haunting essay the explores the toll of childhood sexual trauma on the body and brain.